GSD

5 Best Practices To Make Pull Requests Less Painful

Posted by Heidar Bernhardsson on September 27, 2023

Introduction

In this article we’ll go over some best practices that help ensure good pull requests. Writing good pull requests and having an effective workflow will increase a team’s productivity and minimize frustration. Although a pull request is traditionally considered the final point in the developer workflow, these best practices span the entire development process. We’ll focus on the key points that affect the quality of a pull request.

We’ll cover the importance of good user stories, code testing, code readability, writing good revision control commits, and finally, writing good pull request descriptions.

The importance of good pull requests

Having a culture of writing good pull requests within a team can make a big difference in productivity. If pull requests are small, frequent, and easy to review and test, they will result in pull requests being opened and merged quickly.

On the other hand, having infrequent, big pull requests that bounce back and forth between developers, reviewers, testers and product owners can slow progress down significantly, causing developers to waste a lot of time dealing with merge conflicts and putting out tiny fires everywhere. Cumbersome pull requests also increase the risk of breaking things; since changes are so big, it’s hard to scrutinize all the changes and test them for regressions.

The quality of pull requests in a project is a good overall indicator of how efficient the team’s development practices are. If a team is already writing small pull requests that get merged quickly, it reflects their good workflow and collaborative practices.

However, if the team is struggling with pull requests taking too long to merge, because code reviews are slow and pull requests bounce back and forth a lot, it’s probably a sign that something that can be improved.

User stories

A user story is a short description of a unit of work that needs doing. It’s normally told from the perspective of the user, hence the name. The journey towards a good pull request starts with a well-written user story. It should be scoped to a single thing that a user can do in the system being built.

Breaking down user stories

User stories normally start out very generic and get broken down into smaller, more specific stories as a project progresses. Here’s an example of what a generic user story might look like:

“As a customer, I can log in to the administration system.”

Although that might seem like a reasonable user story, it should be broken down further, because the scope is too wide. It would probably take a developer more than a day to create a fully operational login system. How granularly it gets broken up is up to the team, but a user story should ideally require one day or less of development work. Here’s an example of what one part of this story might look like:

“As a customer, I can input my username and password into a login form and click submit.”

Other stories following up from this one could cover what happens when the user provides invalid input, or what happens after clicking submit. Many teams do this during sprint planning, so everyone on the team gets an overview of upcoming work.

Go vertical

There is one more thing worth mentioning about breaking up user stories that many teams get wrong. When slicing stories, they should be sliced vertically, rather than horizontally.

A vertically sliced story normally requires work on the entire stack: from the views, to any services/libraries, and to the database. A horizontally sliced story will only touch one of those. Consider our user story example from before. Here’s a badly horizontally sliced version.

“As a user, I can have my details stored in the database”

That barely passes as a user story in the first place, but teams often end up structuring the work around the stack, rather than the action being performed. As a result, it can take completing multiple stories to see any real customer-facing value being added.

By creating vertically-sliced stories, the team has a clear picture of what specific tasks need to be completed to add value for the end-user, and the tasks are more discrete and easier to keep track of.

User story dependencies

Ideally, no user story should depend on another user story being done. That way, all work can be done in parallel. In reality, stories depend on each other quite often. It’s important to document which stories are dependent on other stories.

When working with a series of stories that depend on each other, it’s common to end up with a “tower” of pull requests, where developers end up with a series of nested feature branches. The easiest solution to this is to merge the first dependent story before the others are finished. Things don’t always run that smoothly though.

Consider these example branches with three levels of nesting.

master < branch1 < branch2 < branch3

If changes are made in branch1 after branch3 is made, then branch2 has to be rebased on branch1, and then branch3 has to be rebased on branch2. Once branch1 is rebased on master, difficult merge conflicts can can start happening as well.

Ideally this would be resolved from the bottom to the top. Merge branch3 into branch2, then branch2 into branch1 and then finally into master. However, usually this will get merged from old to new, where branch1 will get merged first, then branch2 is rebased on master.

To avoid dealing with situations like this, avoid dependencies whenever possible and when they happen, try to merge the pull requests quickly so that work can continue. In teams where pull requests get dealt with almost immediately, this is not a problem, but if that’s not the case it might be better to notify the team about prioritizing the pull request as it will need building on.

It can be useful to have a special slack channel for GitHub activity. This can be done using the GitHub integration for Slack. This channel can be a good place to highlight team members about pull requests that cannot wait. Bear in mind that highlighting in this manner can be considered disruptive in teams that try to minimize disruptions from Slack.

Estimating stories accurately

Many businesses struggle with this, but it can be vital for planning. We’ve already covered the key element in getting better at this, breaking down stories into something that can be done in a day or less. But that begs the question, how do we know if a story takes a day or less?

A good method for doing this is doing “planning poker”. Before or during sprint planning, have each developer independently vote on how long a story will take. The median of the vote should give a reasonably accurate estimate of how long the story will take. If it’s more than a day, break the story down and try again.

It can take some trial and error to get good at this. Having developers use time tracking to detail time spent on each story is a good way to measure the real time spent on each story and validating estimates. Before the next planning poker, review how far off the previous estimates were and use it as reference to adjust future estimates. Some project management software, such as Jira, has time tracking built in.

Write clear tests

Writing good tests has many benefits. One of them is to make sure the code does what it should. If there are good tests that pass, chances are that the code works. However, this is not a replacement for running code before submitting it to a pull request. Running code in a QA environment can reveal bugs caused by the environment being different, or something that wasn’t tested for.

Tests as documentation

There is another big reason to write tests: tests double as documentation. An experienced developer will look at a user story and start by writing an acceptance test for it. This is another reason good user stories are needed, so developers can write good tests and ultimately good pull requests.

When another developer comes along to review the code someone wrote, it can be helpful if they can look at the tests to see what this pull request covers. Many testing frameworks, such as RSpec, also allow the test output to print out every expectation to state what is happening. Consider the following acceptance test example from RSpec.

RSpec.feature "Widget management", :type => :feature do

scenario "User creates a new widget" do

visit "/widgets/new"

click_button "Create Widget"

expect(page).to have_text("Widget was successfully created.")

end

endLooking at this, the developer reviewing the code will immediately see that this pull request includes changes allowing the user to create widgets. The output from running this test can be seen below. Failed tests would be displayed in red.

Widget management

User creates a new widget

When a pull request is being code reviewed, this also allows the developer reviewing the code to double check if all the requirements of the user stories have been met and tested or if the scope of this pull request goes outside of the original user story.

Write Readable Code

Writing readable code will result in a better pull request, because if code is easy to read, it means it’s easy to review as well. Readable code results in shorter review times and reduces the likelihood of the reviewer needing to ask the author questions.

Code comments

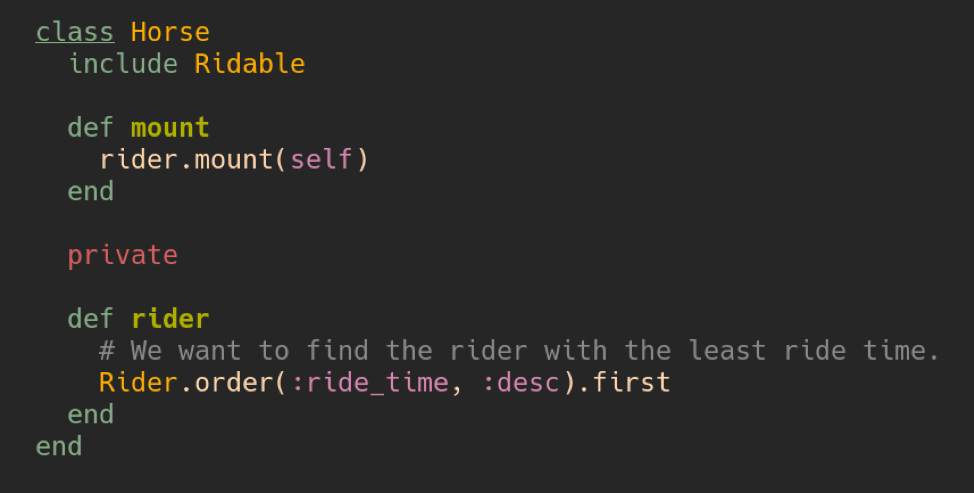

Sometimes our code needs a little help explaining why we are doing something. This can often be resolved by writing descriptive method/function and variable names to make the code read more like spoken language. Another popular solution is to use code comments to explain what the code is doing.

There are split views on code comments. Some teams encourage liberal use of code comments, whereas other teams consider them a code smell. When looking to add a comment to explain code, it’s a good rule to first consider changing the code to be more self documenting. Failing that, adding a comment will probably help the next person who reads the code.

Consider the example in the image above, instead of calling the method rider, we could have called it rider_with_least_ride_time and the comment is no longer required as the intent is clear.

Code comment tags

It might be more descriptive to use code comment tags such as TODO or FIXME to explain the nature of a comment, and why it was left in the first place. If a comment was chosen to explain the code, prefixing the comment with a TODO to improve the code explains to the reviewer and anyone who arrives at it in the future that this needs improving.

Write good commit messages

Writing good commit messages allows others to go through the history of the branch and get an overview of what was done. This requires small and frequent commits. A commit should ideally include a complete, isolated change. This enables developers to safely cherry pick or roll back commits as needed. That’s difficult or impossible to do with big commits, or lots of “work in progress” commits that are incomplete.

When writing commit messages, always stick to the team’s conventions above anything else. To write useful commit messages, it’s good to prefix them with a verb, such as “add”, “remove”, or “fix”, followed by what was done. Keep it short and simple and don’t be scared to use the commit body to provide more information. Here’s some examples.

add login page for administration panel

change route to point to new login page

remove old login page

Some teams prefer to squash a branch into a single commit before merging. The good thing about this is that merge conflicts become much easier to deal with and the commit history is much more succinct. However, this removes a lot of information. If a team is good at doing small, frequent pull requests this can work well.

Pull request creation process

Most teams have some sort of pull request creation process to organize pull requests and make sure everything is documented. An example could be as follows.

- Run the code manually to make sure it works

- Make sure tests document all changes

- Add tags to the pull request

- Update status of user story and link to pull request

- Add reference to user story in pull request

- Update the change log if not done automatically

- Request a review from someone in a non-disruptive manner

These can get pretty long, depending on a team’s workflow. Some of these can be automated, this should be done where possible. However, for the manual ones it can help having a checklist to refer to can be helpful when performing all of these.

GitHub pull request descriptions support interactive checklists and templates. Other similar services might have this too, but this is a great place for these checklists. Another good place can be modeling this workflow in the team’s project management software.

The pull request templates can also have template sections for the developer to fill out to explain what the pull request does. Taking a minute to write a good description of what the pull request does can help the developer performing the code review understand the changes better. This should include at minimum what changes are being introduced and why [6]. As always, follow the team’s template above all.

Conclusion

In this article we covered the key points to submit good pull requests. We discussed how writing good user stories, code, and commit messages all contributes to a good pull request. The key point to take from this article is that the whole development process affects the quality of the work that ends up in a pull request, starting with a user story.

If you want to implement some of these tips in your team, consider starting at the beginning with the user stories, if applicable. Without those, the rest more or less falls apart. Avoid changing everything at once; rather change one thing at a time and make sure the team is happy with the changes before introducing an additional change.

ButterCMS is the #1 rated Headless CMS

Related articles

Don’t miss a single post

Get our latest articles, stay updated!

Heidar is a London based software developer. He specialises in consulting software delivery teams on working together effectively and delivering maintainable software.